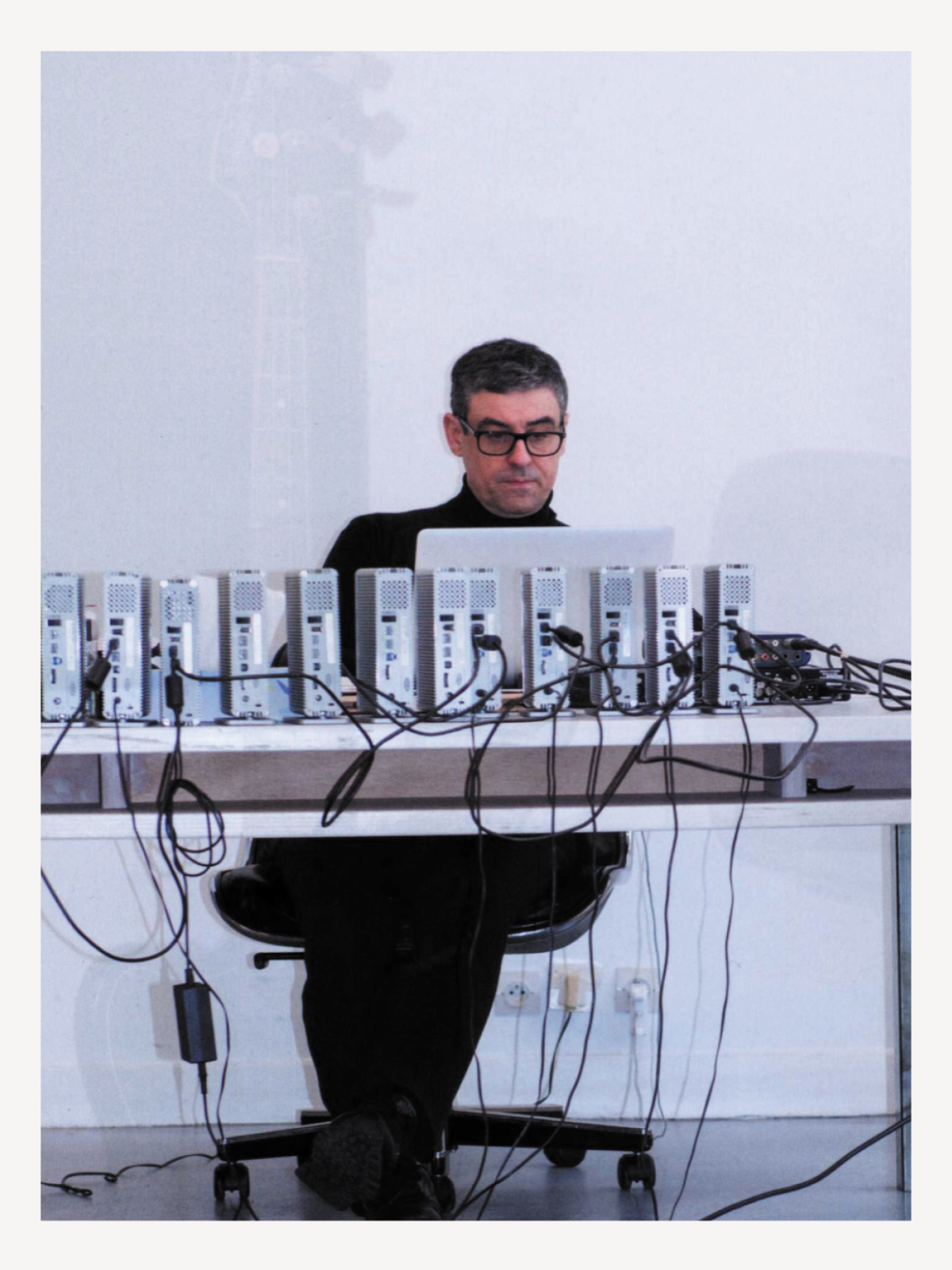

Backstage with Frédéric Sanchez

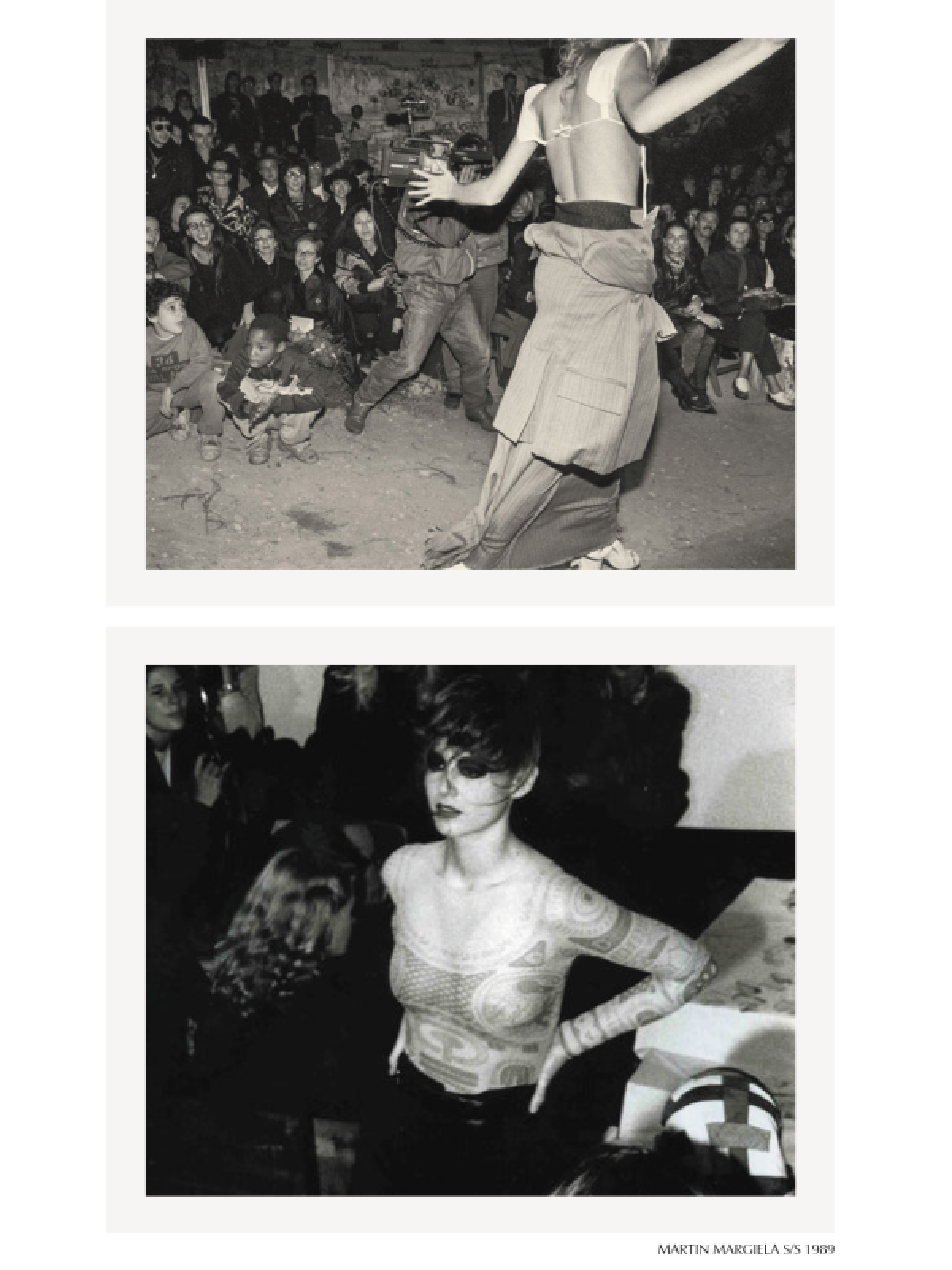

If you’ve ever sat at a fashion show—or watched one on YouTube—it’s likely that you’ve been introduced to the work of Frédéric Sanchez. Since collaborating with Martin Margiela on his 1989 runway debut, the pioneering French sound designer—or illustrator, as he refers to himself—has married the sonic with the sartorial, cementing himself as a bona fide industry icon.

After all, who else can create a seemingly endless soundscape of airy chords and electronic beats in the case of Jil Sander’s catwalks, or so masterfully layer Nirvana’s “I Hate Myself and Want to Die,” a cover of Sinead O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2U,” and Nina Simone’s “I Put a Spell on You” for his ever-loyal collaborator Mrs. Miuccia Prada’s Spring 2018 collection?

Here, Sanchez looks back on his three-decade-plus career, and offers an exclusive playlist for the moment in aural style.

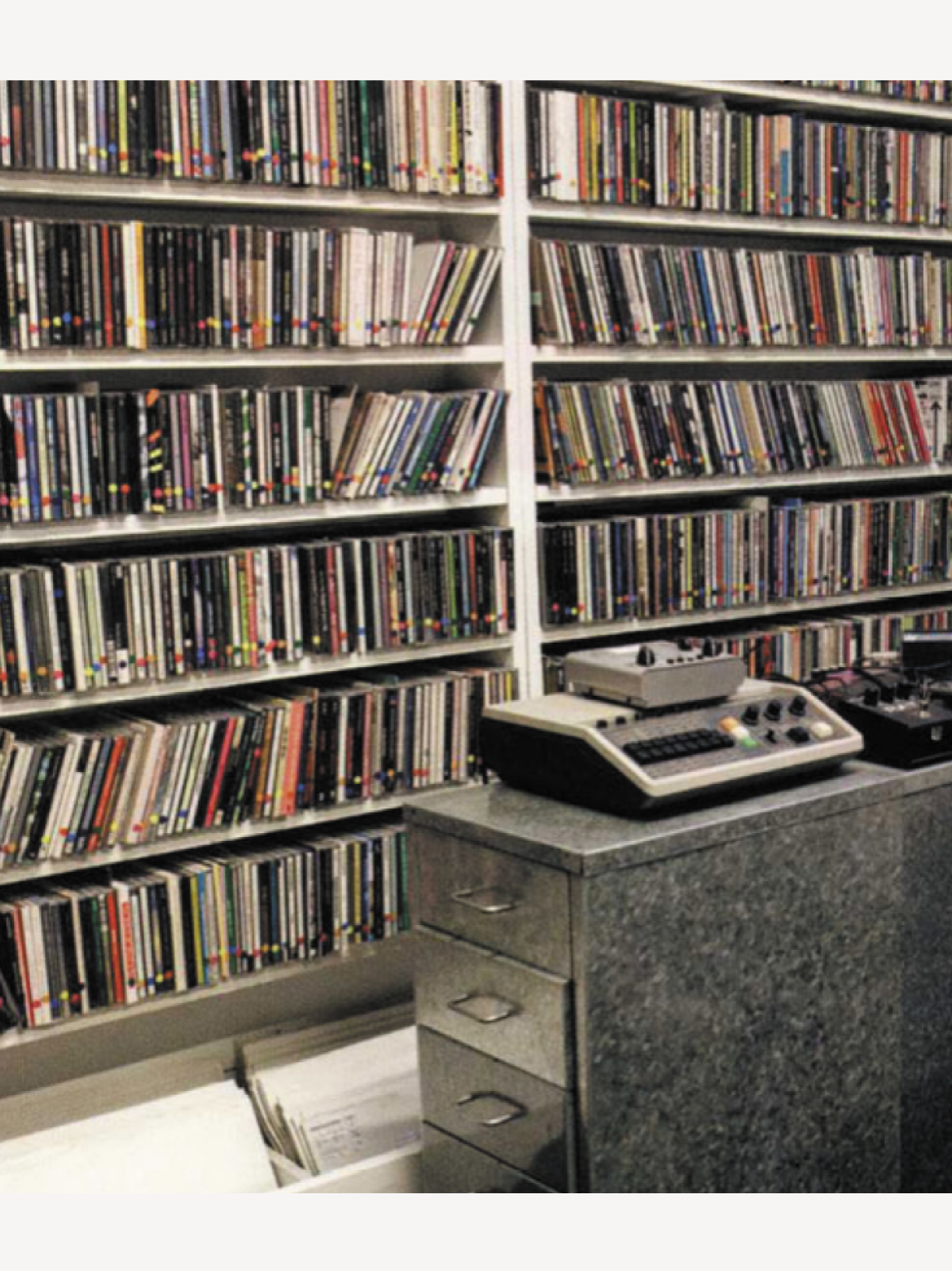

“Music has always been a way for me to talk about myself and to express myself. When I was a teenager I got very interested in the visuals of the records I was listening to and the way musicians, like David Bowie and Roxy Music, made music but also manipulated images. More and more, I realized that with music you could tell stories. But I really didn’t know where it would take me—I didn’t think I’d have a career in it. Actually, I didn’t know at all what I was going to do! I thought that maybe I wanted to work in an artistic field, but I came from a family that had no connection to that.

I was supposed to do very long studies at a university, but instead I became an intern at a big theater in Paris, Théâtre du Châtelet, in the ’80s. They were doing a lot of dance, which was very new. The first show I worked on was Martha Graham, when she was still alive... There were all of these young companies led by people, who were simultaneously very interested in music, fashion, and theater. It was not only one field; it was very multimedia. At the time, the Japanese designers, like Yohji Yamamoto, were doing really beautiful catalogues with new photographers, like Nick Knight and Max Vadukul, and the graphic artist Peter Saville who was also doing the album covers of New Order, Joy Division, and loads of incredible bands. Suddenly, I said, ‘Okay, I’m going to also work in fashion.’ I had another job as a PR assistant to Michèle Montagne who was taking care of Chloé’s then-creative director Martine Sitbon. Once Martine called and said that she was having issues with her music. I was playing records in the studio all the time, so the next day Michèle sent me to see Martine and I brought some with me. At that moment, I thought, ‘I'm going to do something with music.’ A year later, my friend introduced me to Martin Margiela for his first show.

Martin invited me to his place and we had dinner together. I saw how it was, where he was living... It’s my way of working too—I really go inside someone’s head… I remember that there was this table with impeccable cotton napkins, very ironed, and then he started to squeeze the fabric. Suddenly the fabric became old… His whole story was about that: there’s a certain attitude in playing with the past. This was very interesting because music for me is always full of memories. So we started working on this very organic soundtrack to tell the story of the clothes. We played with this idea of a collage of all of these sounds of bad recordings, a record that was scratched.

That was my first soundtrack, and it was not going to be the last. I had found my way and my own technique, which was very new at the time because then, at the end of the ’80s, there was still this couture way of doing shows—they were usually very long, and maybe you’d put on one song after the other very randomly, but it was not like you’d do a strong soundtrack from beginning to end. I’d treat music almost like I was doing a film—not mixing, like a DJ, but something else, something that’s more organic. I gave it a name: an illustration.

Very soon after, in ’89, I was called by Jil Sander. I started working with her in the beginning of the ’90s. It was this fashion house—a mix of something very artistic and something very business-conscious—but she gave me a lot of freedom. Now it was possible to make soundtracks that would express the level of quality that she wanted to create… When I started to work with Prada in the middle of the ’90s I was doing very minimalist soundtracks—I was often using just one song from the beginning to the end, so I was pushing the idea of one strong, focused idea very far.

The soundtracks don’t actually begin with the music; they usually come from conversations. It starts with talking not necessarily about the clothes but perhaps a film or the space of the show, which is very important because how you build a soundtrack is related to its environment. The process is very free and abstract in a way, as is my inspiration, which I catch at a certain moment. I search a lot on the internet and YouTube… Two or three years ago, I was watching a 1976 Nina Simone concert in Switzerland. She was about to sing this song by Janice Ian called “Stars”, but suddenly she stopped and started to say strange things. There was something very sensitive about it—and then when she does start the song you want to cry. I realized she was trying to put her public in a certain state of mind, to build an atmosphere for her audience. I showed it to Hermès creative director Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski and started to mix Simone’s talking with an old Janet Jackson song. It ended up playing during one of the shows. That’s how I build a soundtrack: I enter into the world of a musician and mix it with other things, and suddenly it tells a story.

There was a moment in which I would start working maybe a week before the show, but now I like to work in advance. I like to have the possibility to do something and come back and do something else, to search and to evolve until the moment of the show. For the past six or seven years, I’ve also begun composing music for social media because usually we can’t use the same soundtrack that we play in the live shows. I developed the idea of doing something that’s equally interesting but something that’s completely composed. It’s another way of working, so you need a lot of time.

In a way, the sounds and the music that I work with are like a sense—it’s like putting on a perfume. With different scents you create a perfume, and with different music you create a soundtrack. Like perfume, the soundtrack becomes memories, sensitive things. It’s a sensation. Jil was always talking about how a song really surrounds you when you listen in a car. It’s true—often, in a car the music has a lot of bass, and there’s something very sensual in the way that the sound moves. With Jil, we talked more about sounds and the quality of the sounds than music. You talk about the quality of the music, you talk also about the quality of the clothes. It’s a sensation, too.

Every first time that I’ve worked with a house has been my favorite project. My first show at Margiela was incredible. I also got very excited in the middle of the ’90s when I decided to go to work in New York. It was not something that a lot of people were doing at the time, but I really wanted to work with Calvin Klein. At the same time, I started to work with Marc Jacobs. Then, I started working on exhibitions, like the Jil Sander retrospective in Frankfurt in 2017. It’s not often that a museum gives someone the possibility to do something with sound. It was a huge exhibition—3,000 square meters. I put sounds everywhere in the space and created software programs to really make the sound move. It was like an invisible architecture surrounding people with sounds moving and telling the stories. This is when I really developed the idea of the perfume and this idea that suddenly the place becomes very sensitive because of its sounds. I think I got very lucky because music is a passion that I’ve transformed into work. When I started my career suddenly I could create using all these songs that I’ve listened to for a very long time. What’s interesting, though, is that I’ve created the work that I’m doing. I do my own things, my own techniques. It’s my own way of working, which is very great.”

as told to Zoe Ruffner

At ReSee, every one of our vintage pieces comes with a story. This is, in large part, thanks to our unmatched community of consignors.

Though parting with such sartorial treasures may not be easy, the exceptional personal care we put into ensuring that they will go on to live a second (or, sometimes even, a third, fourth, or fifth) life offers a thrill — one rivaled only by that of the besotted shopper who adds them to her wardrobe.

Sell with us